Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 2002

Les thèmes de la géopolitique et de l'espace russe dans la vie culturelle berlinoise de 1918 à 1945

Karl Haushofer, Oskar von Niedermayer & Otto Hoetzsch

Intervention de Robert Steuckers à la 10ième Université d'été de «Synergies Européennes», Basse-Saxe, août 2002

Analyse : Karl SCHLÖGEL, Berlin Ostbahnhof Europas - Russen und Deutsche in ihrem Jarhhundert, Siedler, Berlin, 368 S., DM 68, 1998, ISBN 3-88680-600-6.

En 1922, après l'effervescence spartakiste qui venait de secouer Berlin et Munich, un an avant l'occupation franco-belge de la Ruhr, le Général d'artillerie bavarois Karl Haushofer, devenu diplômé en géographie, est considéré, à l'unanimité et à juste titre, comme un spécialiste du Japon et de l'espace océanique du Pacifique. Son expérience d'attaché militaire dans l'Empire du Soleil Levant, avant 1914, et sa thèse universitaire, présentée après 1918, lui permettent de revendiquer cette qualité. Haushofer entre ainsi en contact avec deux personnalités soviétiques de premier plan: l'homme du Komintern à Berlin, Karl Radek, et le Commissaire aux affaires étrangères, Georgi Tchitchérine (qui signera les accords de Rapallo avec Rathenau). Dans quel contexte cette rencontre a-t-elle eu lieu? Le Japon et l'URSS cherchaient à aplanir leurs différends en entamant une série de négociations où les Allemands ont joué le rôle d'arbitres. Ces négociations portent essentiellement sur le contrôle de l'île de Sakhaline. Les Japonais réclament la présence de Haushofer, afin d'avoir, à leurs côtés "une personnalité objective et informée des faits". Les Soviétiques acceptent que cet arbitre soit Karl Haushofer, car ses écrits sur l'espace pacifique —négligés en Allemagne depuis que celle-ci a perdu la Micronésie à la suite du Traité de Versailles— sont lus avec une attention soutenue par la jeune école diplomatique soviétique. Qui plus est, avec la manie hagiographique des révolutionnaires bolcheviques, Haushofer a connu les frères Oulianov (Lénine) à Munich avant la première guerre mondiale; il aimait en parler et relatera plus tard ce fait dans ses souvenirs. L'intérêt soviétique pour la personne du Général Haushofer durera jusqu'en 1938, où, changement brusque d'attitude lors des grandes procès de Moscou, le Procureur réclame la condamnation de Sergueï Bessonov, qu'il accuse d'être un espion allemand, en contact, prétend-il, avec Haushofer, Hess et Niedermayer (cf. infra). Les mêmes accusations avaient été portées contre Radek, qui finira exécuté, lors des grandes purges staliniennes.

Ces trois faits d'histoire —la présence de Haushofer lors des négociations entre Japonais et Soviétiques, le contact, sans doute fort bref et parfaitement anodin, entre Haushofer et Lénine, les condamnations et exécutions de Radek et de Bessonov— indiquent qu'indépendamment des étiquettes idéologiques de "gauche" ou de "droite", la géopolitique, telle qu'elle est théorisée par Haushofer à Munich et à Berlin dans les années 20, ne s'occupe que du rapport existant entre la géographie et l'histoire; elle est donc considérée comme une démarche scientifique, comme un savoir pratique et non pas comme une spéculation idéologique ou occultiste, véhiculant des fantasmes ou des intérêts. A l'époque, on peut parler d'une véritable "Internationale de la géopolitique", transcendant largement les étiquettes idéologiques, tout comme aujourd'hui, un savoir d'ordre géopolitique, éparpillé dans une multitude d'instituts, commence à se profiler partout dans un monde où les grands enjeux géopolitiques sont revenus à l'ordre du jour : la question des Balkans, celle de l'Afghanistan, remettent à l'avant-plan de l'actualité toutes les grandes thématiques de la géopolitique, notamment celles qu'avaient soulignées Mackinder et Haushofer.

Une démarche factuelle et matérielle, sans dérive occultiste

A partir de 1924, Haushofer publie sa Zeitschrift für Geopolitik (ZfG; "Revue pour la géopolitique"), où il met surtout l'accent sur l'espace du Pacifique, comme l'attestent ses articles et sa chronique, rédigée notamment grâce à des rapports envoyés par des correspondants japonais. La teneur de cette revue est donc politique et géographique pour l'essentiel, contrairement aux bruits qui ont couru pendant des décennies après 1945, et qui commencent heureusement à s'atténuer; ces "bruits" évoquaient une fantasmagorique dimension "ésotérique" de la Zeitschrift für Geopolitik (ZfG); on a raconté que Haushofer appartenait à toutes sortes de sectes ésotériques ou occultes (voire occultistes). Ces allégations sont bien sûr complètement fausses. De plus, l'intérêt porté à Haushofer et à ses thèses sur l'espace du Pacifique par la jeune diplomatie soviétique, par Radek et Tchitchérine, est un indice complémentaire —et de taille!— pour attester de la nature factuelle et matérielle de ses écrits; les sectes étant par définition irrationnelles, comment un homme, que l'on dit plongé dans cet univers en marge de toute rationalité scientifique, aurait pu susciter l'intérêt et la collaboration active de marxistes matérialistes et historicistes? De marxistes qui tentent d'expurger toute irrationalité de leurs démarches intellectuelles? L'accusation d'occultisme portée à l'encontre de Haushofer est donc une contre-vérité propagandiste, répandue par les services et les puissances qui ont intérêt à ce que son œuvre demeure inconnue, ne soit plus consultée dans les chancelleries et les états-majors. Il va de soi qu'il s'agit des puissances qui ont intérêt à ce que le grand continent eurasien ne soit pas organisé ni aménagé territorialement jusqu'en ses régions les plus éloignées de la mer.

Le principal ouvrage géopolitique et scientifique de Haushofer est donc sa Geopolitik des Pazifischen Raumes ("Géopolitique de l'espace pacifique"), livre de référence méticuleux qui se trouvait en permanence sur le bureau de Radek, à Berlin comme à Moscou. Karl Radek jouait le rôle du diplomate du PCUS ("Parti communiste d'Union Soviétique"). Il a cependant plaidé, au moment où les Français condamnent à mort et font fusiller l'activiste nationaliste allemand Albert Leo Schlageter, pour un front commun entre nationaux et communistes contre la puissance occidentale occupante. Plus tard, Radek sera nommé Recteur de l'Université Sun-Yat-Sen à Moscou, centre névralgique de la nouvelle culture politique internationale que les Soviets entendent généraliser sur toute la planète. Radek organisera, au départ de cette université d'un genre nouveau, un échange permanent entre universitaires, dont le savoir est en mesure de forger cette nouvelle culture diplomatique internationale.

Trois figures emblématiques

Dans le cadre de cette Université Sun-Yat-Sen , trois figures emblématiques méritent de capter aujourd'hui encore notre attention, tant leurs démarches peuvent encore avoir une réelle incidence sur toute réflexion actuelle quant au destin de la Russie, de l'Europe, de l'Asie centrale et quant aux théories générales de la géopolitique: Mylius Dostoïevski, Richard Sorge et Alexander Radós.

Mylius Dostoïevski est le petit-fils du grand écrivain russe. Qui, rappelons-le, a jeté les bases d'une révolution conservatrice en Russie, au-delà des limites de la slavophilie du début du 19ième siècle, et a consolidé, par ricochet, la dimension russophile de la révolution conservatrice allemande, par le biais de ses réflexions consignées dans son Journal d'un écrivain, ouvrage capital qui sera traduit en allemand par Arthur Moeller van den Bruck. Mylius Dostoïevski s'était spécialisé en histoire et en géographie du Japon, de la Chine et de l'espace maritime du Pacifique. Il appartiendra à la jeune garde de la diplomatie soviétique et sera un lecteur attentif de la ZfG; pour rendre la politesse à ces jeunes géographes soviétiques, selon sa courtoisie habituelle, Karl Haushofer rendra toujours compte, avec précision, des évolutions diverses de la nouvelle géopolitique soviétique. Il estimait que les Allemands de son temps devaient en connaître les grandes lignes et la dynamique.

Richard Sorge, autre lecteur de la ZfG, était un espion soviétique en Extrême-Orient. On connaît son rôle pendant la seconde guerre mondiale. En 1933, au moment où Hitler prend le pouvoir en Allemagne, Sorge était en contact avec l'école géopolitique de Haushofer. Il le restera, en dépit du changement de régime et en dépit des options anti-communistes officielles, preuve supplémentaire que la géopolitique se situe bien au-delà des clivages idéologiques et politiciens. Au cours des années qui suivirent la "Machtübernahme" de Hitler, il écrivit de nombreux articles substantiels dans la ZfG. Sa connaissance du monde extrême-oriental —et elle seule— justifiait cette collaboration.

Alexander Radós et "Pressgeo"

Indubitablement, le principal disciple soviétique de Karl Haushofer a été l'Israélite hongrois Alexander Radós, un géographe de formation, qui a servi d'espion au profit de la jeune URSS, notamment en Suisse, plaque tournante de nombreux contacts officieux. Radós est l'homme qui a forgé tous les nouveaux concepts de la géographie politique soviétique. Il est, entre autres, celui qui forgea la dénomination même d'«Union des Républiques Socialistes Soviétiques». Radós fut principalement un cartographe, qui a commencé sa carrière en établissant des cartes du trafic aérien, lesquelles constituaient évidemment une innovation à son époque. Il enseignait à l'«Ecole marxiste de formation des Travailleurs» ("Marxistische Arbeiterschulung"). Il fonde ensuite la toute première agence de presse cartographique du monde, qu'il baptise "Pressgeo", où travaillera notamment une future célébrité comme Arthur Koestler. La fondation de cette agence correspond parfaitement aux aspirations de Haushofer, qui voulait vulgariser —et diffuser au maximum au sein de la population— un savoir pragmatique d'ordre géographique, historique et économique, assorti d'un esprit de défense. La carte, esquisse succincte, instrument didactique de premier ordre, sert l'objectif d'instruire rapidement les esprits décisionnaires des armées et de la diplomatie, ainsi que les enseignants en histoire et en science politique qui doivent communiquer vite un savoir essentiel et vital à leurs ouailles.

Haushofer parlait aussi, en ce sens, de "Wehrgeographie", de "géographie défensive", soit de "géographie militaire". L'objectif de cette science pragmatique était de synthétiser en un simple coup d'œil cartographique toute une problématique de nature stratégique, récurrente dans l'histoire. Pédagogie et cartographie formant les deux piliers majeurs de la formation politique des élites et des masses. Yves Lacoste, en France aujourd'hui, suit une même logique, en se référant à Elisée Reclus, géographe dynamique, réclamant une pédagogie de l'espace, dans une perspective qu'il voulait révolutionnaire et "anarchique". Lacoste, comme Haushofer, a parfaitement conscience de la dimension militaire de la géographie (et, a fortiori, de la "Wehrgeographie"), quand il écrit, en faisant référence aux premiers cartographes militaires de la Chine antique: «La géographie, ça sert à faire la guerre!».

De l'utilité pédagogique de la cartographie

Michel Foucher, professeur à Lyon, dirige aujourd'hui un institut géographique et cartographique, dont les cartes, très didactiques, illustrent la majeure partie des organes de presse français, quand ceux-ci évoquent les points chauds de la planète. Dans ce même esprit pluridisciplinaire, à volonté clairement pédagogique, —qui, en France et en Allemagne, va de Haushofer à Lacoste et à Foucher— Alexander Radós, leur précurseur soviétique, publie, en URSS et en Allemagne, en 1930, un Atlas für Politik, Wirtschaft und Arbeiterbewegung ("Atlas de la politique, de l'économie et du mouvement ouvrier"). Radós est ainsi le précurseur d'une manière innovante et intéressante de pratiquer la géographie politique, de mêler, en d'audacieuses synthèses, un éventail de savoirs économiques, géographiques, militaires, topographiques, géologiques, hydrographiques, historiques. Les synthèses, que sont les cartes, doivent servir à saisir d'un seul coup d'œil des problématiques hautement complexes, que le simple texte écrit, trop long à assimiler, ne permet pas de saisir aussi vite, d'exprimer sans détours inutiles. Ce fut là un grand pas en avant dans la pédagogie scientifique et politique, dans le sens inauguré, un siècle auparavant, par le géographe Carl Ritter.

Cette cartographie facilite le travail du militaire, du géographe et de l'homme politique; elle permet, comme le soulignait Karl August Wittfogel, de sortir d'une impasse de la vieille science géographique traditionnelle (et "réactionnaire" pour les marxistes), où, systématiquement, on avait négligé les macro-processus enclenchés par le travail de l'homme et, ainsi, le caractère "historique-plastique" de ce que l'on croyait être des "faits éternels de nature". C'est dans cette position épistémologique fondamentale, qu'au-delà des clivages idéologiques, fruits d'"éthiques de la conviction" aux répercussions calamiteuses, se rejoignent Elisée Reclus, Haushofer, Radós, Wittfogel, Lacoste et Foucher. Wittfogel , qui se pose comme révolutionnaire, reconnaît cette "plasticité historique" dans l'œuvre du "géopolitologue bourgeois" Karl Haushofer. Les deux écoles, l'haushoférienne et la marxiste, veulent inaugurer une géographie dynamique, où l'espace n'est plus posé comme un bloc inerte et immobile, mais s'appréhende comme un réseau dense de relations, de rapports, de mouvements, en perpétuelle effervescence (on songe tout naturellement au "rhizome" de Gilles Deleuze, qui inspire les "géophilosophes" italiens actuels). Au sein de ce réseau toujours agité, le temps peut apporter des époques de repos, de plus grande quiétude, comme il peut injecter du dynamisme, de la violence, des bouleversements, qui contraignent les personnalités politiques de valeur à œuvrer à des redistributions de cartes. Le travail de l'homme, qui domestique certains espaces en les aménageant et en créant des moyens de communication plus rapides, est un travail proprement "révolutionnaire"; les hommes politiques qui refusent d'aménager l'espace, dans un esprit de défense territoriale ou dans l'esprit d'assurer aux générations futures communications et ressources, sont des "réactionnaires", des lâches qui préfèrent de lents pourrissements à la dynamique de transformation. Des capitulards qui font ainsi le jeu pervers des thalassocraties.

Par conséquent, évoquer des hommes comme Mylius Dostoïevski, Richard Sorge, Alexander Radós ou Karl August Wittfogel, nous apparaît très utile, intellectuellement et méthodologiquement, car cela prouve:

◊ que l'intérêt général pour la géopolitique aujourd'hui ne peut plus être mis en équation avec un intérêt malsain pour le passé national-socialiste (contexte dans lequel Haushofer a dû œuvrer);

◊ qu'aucune morbidité d'ordre ésotérique ou occultiste ne se repère dans l'œuvre de Haushofer et de ses disciples allemands ou soviétiques;

◊ que ces écoles ont posé d'important jalons dans le développement de la science politique, de la géographie et de la cartographie;

◊ qu'elles ont laissé en héritage un bagage scientifique de la plus haute importance;

◊ que nous devrions davantage nous intéresser aux développements de la géopolitique soviétique des années 20 et 30 (et analyser l'œuvre de Radós, par exemple).

Oskar von Niedermayer, le "Lawrence allemand"

Outre Haushofer, une approche du savoir géopolitique, tel qu'il sera déployé à Berlin dans les années 20, 30 et 40, ne peut omettre d'étudier la figure du Chevalier Oskar von Niedermayer, celui que l'on avait surnommé, le "Lawrence d'Arabie" allemand. Né en 1885, Oskar von Niedermayer embrasse la carrière d'officier, mais ne se contente pas des simples servitudes militaires. Il étudie à l'université les sciences naturelles physiques, la géographie et les langues iraniennes (ce qui lui permettra d'avoir des contacts suivis avec la Communauté religieuse Ba'hai, qui, à l'époque, était quasiment la seule porte ouverte de l'Iran sur l'Occident). De 1912 à 1914, il effectue un long voyage en Perse et en Inde. Il sera ainsi le premier Européen à traverser de part en part le désert de sable du Lout (Dacht-i-Lout). En 1914, quand éclate la première guerre mondiale, Oskar von Niedermayer, accompagné par Werner Otto von Henting, sillonne les montagnes d'Afghanistan pour inciter les tribus afghanes à se soulever contre les Anglais et les Russes, afin de créer un "abcès de fixation", obligeant les deux puissances ennemies de l'Allemagne à dégarnir partiellement leurs fronts en Europe, dans le Caucase et en Mésopotamie. Cette mission sera un échec. En 1919, Niedermayer se retrouve dans les rangs du Corps Franc du Colonel Chevalier Franz von Epp qui écrase la République des Conseils de Munich. En dépit de son rôle dans l'aventure de ce Corps Franc anti-communiste, Niedermayer est nommé dans la foulée officier de liaison de la Reichswehr auprès de la nouvelle Armée Rouge à Moscou. Dans ce contexte, il est intéressant de noter qu'il était, avant toutes choses, un expert de l'Afghanistan, des idiomes persans et de toute cette zone-clef de la géostratégie mondiale qui va de la rive sud de la Caspienne à l'Indus. C'est donc Niedermayer qui négociera avec Trotski et qui visitera, pour le compte de la Reichswehr, dans la perspective de la future coopération militaire entre les deux pays, les usines d'armement et les chantiers navals de Petrograd (devenue "Leningrad"). Oskar von Niedermayer a donc été l'une des chevilles ouvrières de la coopération militaire et militaro-industrielle germano-russe des années 20. En 1930, il devient professeur de "Wehrgeographie" à Berlin.

Outre Haushofer, une approche du savoir géopolitique, tel qu'il sera déployé à Berlin dans les années 20, 30 et 40, ne peut omettre d'étudier la figure du Chevalier Oskar von Niedermayer, celui que l'on avait surnommé, le "Lawrence d'Arabie" allemand. Né en 1885, Oskar von Niedermayer embrasse la carrière d'officier, mais ne se contente pas des simples servitudes militaires. Il étudie à l'université les sciences naturelles physiques, la géographie et les langues iraniennes (ce qui lui permettra d'avoir des contacts suivis avec la Communauté religieuse Ba'hai, qui, à l'époque, était quasiment la seule porte ouverte de l'Iran sur l'Occident). De 1912 à 1914, il effectue un long voyage en Perse et en Inde. Il sera ainsi le premier Européen à traverser de part en part le désert de sable du Lout (Dacht-i-Lout). En 1914, quand éclate la première guerre mondiale, Oskar von Niedermayer, accompagné par Werner Otto von Henting, sillonne les montagnes d'Afghanistan pour inciter les tribus afghanes à se soulever contre les Anglais et les Russes, afin de créer un "abcès de fixation", obligeant les deux puissances ennemies de l'Allemagne à dégarnir partiellement leurs fronts en Europe, dans le Caucase et en Mésopotamie. Cette mission sera un échec. En 1919, Niedermayer se retrouve dans les rangs du Corps Franc du Colonel Chevalier Franz von Epp qui écrase la République des Conseils de Munich. En dépit de son rôle dans l'aventure de ce Corps Franc anti-communiste, Niedermayer est nommé dans la foulée officier de liaison de la Reichswehr auprès de la nouvelle Armée Rouge à Moscou. Dans ce contexte, il est intéressant de noter qu'il était, avant toutes choses, un expert de l'Afghanistan, des idiomes persans et de toute cette zone-clef de la géostratégie mondiale qui va de la rive sud de la Caspienne à l'Indus. C'est donc Niedermayer qui négociera avec Trotski et qui visitera, pour le compte de la Reichswehr, dans la perspective de la future coopération militaire entre les deux pays, les usines d'armement et les chantiers navals de Petrograd (devenue "Leningrad"). Oskar von Niedermayer a donc été l'une des chevilles ouvrières de la coopération militaire et militaro-industrielle germano-russe des années 20. En 1930, il devient professeur de "Wehrgeographie" à Berlin.

Le "marais" et ses éthiques de conviction

La principale leçon qu'il tire de ses activités politiques et diplomatiques est une méfiance à l'endroit des politiciens du "centre", du "marais", incapables de comprendre les grands ressorts de la politique internationale, du "Grand Jeu". Ses critiques s'adressaient surtout aux sociaux-démocrates et aux centristes de tous plumages idéologiques; avec de tels personnages, il est impossible, constate von Niedermayer dans un rapport où il ne cache pas son amertume, d'articuler sur le long terme une politique étrangère durable, rationnelle et constante. Il les accuse de tout critiquer publiquement, par voie de presse; de cette façon, aucune diplomatie secrète n'est encore possible. Pire, estime-t-il, par le comportement délétère de ces bateleurs sans épine dorsale politique solide, aucun ressort habituel de la diplomatie inter-étatique ne fonctionne encore de manière optimale. Car les éthiques de conviction (terminologie de Max Weber: "Gesinnungsethik") qui animent toutes les vaines agitations politiciennes de ces gens-là, altèrent l'esprit de retenue, de sérieux et de service, qui est nécessaire pour faire fonctionner une telle diplomatie traditionnelle. La priorité accordée aux convictions revient à trahir les intérêts fondamentaux de l'Etat et de la nation. L'amertume de Niedermayer est née à la suite d'un incident au Reichstag, où le socialiste Scheidemann, animé par un pacifisme irréaliste et de mauvais aloi, avait dénoncé un accord militaire secret entre l'URSS et le Reich, sous prétexte que le commerce et l'échange d'armements ne sont pas "moraux". Le lendemain, comme par hasard, la presse londonienne à l'unisson, reprend l'information et amorce une propagande contre les deux puissances continentales, qui avaient contourné les clauses de Versailles relatives aux embargos. Cet incident montre aussi que bon nombre de journalistes servent des intérêts étrangers à leur pays. En cela, rien n'a changé aujourd'hui: les Etats-Unis bénéficient de l'appui inconditionnel de la plupart des ténors de la presse parisienne.

Youri Semionov, spécialiste de la Sibérie

Dans les années 30, Niedermayer rencontre Youri Semionov, Russe blanc en exil et spécialiste de l'économie, de la géographie, de la géologie et de l'hydrographie sibériennes. Semionov est l'auteur d'un ouvrage, toujours d'actualité, toujours compulsé en haut lieu, sur les trésors de la géologie sibérienne. Egalement spécialiste de l'empire colonial français, Semionov a compilé ses réflexions successives dans un volume dont la dernière édition allemande date de 1975 (cf. Juri Semjonow, Erdöl aus dem Osten - Die Geschichte der Erdöl- und Erdgasindustrie in der UdSSR, Econ Verlag, Wien/Düsseldorf, 1973 & Sibirien - Schatzkammer des Ostens, Econ Verlag, Wien/Düsseldorf, 1975). Né en 1894 à Vladikavkaz dans le Caucase, Youri Semionov a étudié à l'Université de Moscou, avant d'émigrer en 1922 à Berlin, où il enseignera l'histoire et la géographie de la Russie, et plus particulièrement celles des territoires sibériens. Après la chute du IIIe Reich, il émigre en 1947 en Suède, où il enseignera à Uppsala et finira ses jours. Dans Sibirien - Schatzkammer des Ostens, il retrace toutes les étapes de l'histoire de la conquête russe des territoires situés au-delà de l'ex-capitale des Tatars, Kazan. Il démontre que la conquête de tout le cours de la Volga, de Kazan à Astrakhan, permet à la Russie de spéculer sur une éventuelle conquête des Indes. Semionov replace tous ces faits d'histoire dans une perspective géopolitique, celle de l'organisation du Grand Continent, de la Mer Blanche au Pacifique. Les chapitres sur le 19ième siècle sont particulièrement intéressants, notamment quand il décrit la situation globale après la décision du Tsar Alexandre III de faire financer la construction d'un chemin de fer transsibérien.

Cet extrait du livre de Semionov (pp. 356-357) résume parfaitement cette situation : «Nous savons que toute la politique de "concentration des forces sur le continent", telle celle que l'on avait envisagée en Russie, provoquait une inquiétude faite de jalousie en Angleterre. Tout mouvement de la Russie en Asie y était considéré comme une menace pesant sur l'Inde. L'Amiral Sterling a vu cette menace se concrétiser dès l'installation de la présence russe le long du fleuve Amour. L'écrivain anglais, oublié aujourd'hui, mais très connu à l'époque, Th. T. Meadows, évoquait en 1856, dans un de ses écrits, un "futur Alexandre le Grand" russe, qui s'en irait conquérir la Chine, puis, sans difficulté aucune, détruirait l'empire britannique et soumettrait le monde entier. Ce cri d'alarme pathétique, répercuté par la presse anglaise, est apparu soudain très réaliste, lorsque, dans les années 80 du 19ième siècle, les Russes avancent en Asie centrale et s'approchent de la frontière afghane. En 1884, se déroule le fameux "incident afghan"; un détachement russe s'empare d'un point contesté sur la frontière; ensuite, les Afghans, qui agissaient sur ordre des Anglais, attaquent ce poste, mais sont battus et dispersés par les Russes. Le premier ministre britannique Gladstone déclare, face au Parlement de Londres, que la guerre avec la Russie est désormais inévitable. Seul le refus de Bismarck, de soutenir les Anglais, empêcha, à l'époque, le déclenchement d'une guerre anglo-russe». Toute l'actualité récente semble résumée dans ce bref extrait.

Les chapitres consacrés à l'œuvre de Witte, père du Transsibérien, sont également lumineux. Semionov rappelle que Witte est un disciple de l'économiste Friedrich List, théoricien de l'aménagement des grands espaces. Il existait, avant la première guerre mondiale et avant la guerre russo-japonaise, une véritable idée grande continentale. Elle était partagée en France (Henri de Grossouvre nous a rappelé l'œuvre de Gabriel Hanotaux), en Allemagne (avec le souvenir de Bismarck) et en Chine, avec Li Hung-Tchang, qui négociera avec Witte. L'Angleterre réussira à briser cette unité, ce qui entraînera le cortège sanglant de toutes les guerres du 20ième siècle.

Oskar von Niedermayer rencontre également le Professeur Otto Hoetzsch, dont nous allons retracer l'itinéraire dans la suite de cette intervention. En dépit de leurs itinéraires bien différents et de leurs options idéologiques divergentes, Haushofer, Niedermayer, Semionov et Hoetzsch se complètent utilement et la lecture simultanée de leurs œuvres nous permet de saisir toute la problématique eurasienne, sans la mutiler, sans rien omettre de sa complexité.

Du professorat à la 162ième Division

En 1937, Hitler ordonne la fondation d'un "Institut für allgemeine Wehrlehre" (= "Institut pour les doctrines générales de défense"). Niedermayer, bien que sceptique, servira loyalement cette nouvelle institution d'Etat, dont l'objectif, recentré sur l'ethnologie vu l'intérêt des nationaux-socialistes pour les questions raciales, est d'étudier les rapports mutuels entre peuple(s) et espace(s). Hostile à la "Gesinnungsethik" des nationaux socialistes, comme il avait été hostile à celles des sociaux démocrates ou des centristes, Niedermayer proteste contre les campagnes de diffamation orchestrées contre des professeurs que l'on décrit comme des "intellectuels apolitiques", comportement hitlérien qui trouve parfaitement son pendant dans les campagnes de diffamation orchestrées par un certain journalisme contemporain contre ceux qui demeurent sceptiques face aux projets d'éradiquer l'Irak, la Libye ou la Serbie et d'appuyer des bandes mafieuses comme celles de l'UÇK ou du complexe militaro-mafieux turc. Aujourd'hui, on ne traite pas ceux qui entendent raison garder d'"intellectuels apolitiques", mais d'"anti-démocrates".

De la prison de Torgau à la Loubianka

Comme la plupart des experts ès-questions russes de son temps, Niedermayer déplore la guerre germano-soviétique, déclenchée en juin 1941. En 1942, sur la suggestion de Claus von Stauffenberg, futur auteur de l'attentat du 20 juillet 1944 contre Hitler, Niedermayer est nommé chef de la 162ième Division d'Infanterie de la Wehrmacht, où servent des volontaires et des légionnaires de souche turque (issus des peuples turcophones d'Asie centrale). Cette unité connaît des fortunes diverses, mais l'échec de la politique nationale-socialiste à l'Est, accentue considérablement le scepticisme de Niedermayer. Stationné en Italie avec les restes de sa division, il critique ouvertement la politique menée par Hitler sur le territoire de l'Union Soviétique. Ce qui conduit à son arrestation; il est interné à Torgau sur l'Elbe. Quand les troupes américaines entrent dans la ville, il quitte la prison et est arrêté par des soldats soviétiques qui le font conduire immédiatement à Moscou, où il séjourne dans la fameuse prison de la Loubianka. Il y mourra de tuberculose en 1948.

La mort de Niedermayer ne clôt pas son "dossier", dans l'ex-URSS. En 1964, les autorités soviétiques utilisent les textes de ses dépositions à Moscou en 1945 pour réhabiliter le Maréchal Toukhatchevski. Il faudra attendra 1997 pour que Niedermayer soit lui-même totalement réhabilité. Donc lavé de toutes les accusations incongrues dont on l'avait chargé.

Le pivot indien de l'histoire et la nécessité du "Kontinentalblock"

Nous avons énuméré bon nombre de faits biographiques de Niedermayer, pour faire mieux comprendre le noyau essentiel de sa démarche d'iranologue, d'explorateur du Dacht-i-Lout, d'agitateur allemand en Afghanistan et de commandeur de la Division turcophone de la Wehrmacht. Deux idées de base animaient l'action de Niedermayer: 1) l'idée que l'Inde était le pivot de l'histoire mondiale; 2) la conscience de la nécessité impérieuse de construire un bloc continental (eurasien), le fameux "Kontinentalblock" de Karl Haushofer (projet qu'il a très probablement repris des hommes d'Etats japonais du début du 20ième siècle, tels le Prince Ito, le Comte Goto et le Premier Ministre Katsura, avocats d'une alliance grande continentale germano-russo-japonaise). Si Niedermayer reprend sans doute cette idée de "bloc continental" directement de l'œuvre de Haushofer, sans remonter aux sources japonaises —qu'il devait sûrement ignorer— l'idée de l'Inde comme "pivot de l'histoire" lui vient très probablement du Général Andreï Snessarev, officier tsariste passé aux ordres de Trotski, pour devenir le chef d'état-major de l'Armée Rouge. Ce général, hostile aux thalassocraties anglo-saxonnes, représentant d'un idéal géopolitique grand continental transcendant le clivage blancs/rouges, se plaisait à répéter: «Si nous voulons abattre la tyrannie capitaliste qui pèse sur le monde, alors nous devons chasser les Anglais d'Inde».

Principes thalassocratiques, libéralisme à l'occidentale, permissivité politique et morale, capitalisme dont les ressorts annihilent systématiquement les traditions historiques et culturelles (cf. Dostoïevski et Moeller van den Bruck), logique marchande, étaient synonymes d'abjection pour cet officier traditionnel: peu importe qu'on les combatte sous une étiquette blanche/traditionaliste ou sous une étiquette rouge/révolutionnaire. Les étiquettes sont des "convictions" sans substance: seule importe une action constante visant à réduire et à détruire les forces dissolvantes de la modernité marchande, car elles conduisent le monde au chaos et les peuples à une misère sans issue. Comme nous le constatons encore plus aujourd'hui qu'à l'époque, l'industriel, le négociant et le banquier, avec leur logique d'accumulation monstrueuse, apparaissent comme des êtres aussi abjects qu'inférieurs, foncièrement malfaisants, pour cet officier supérieur russe et soviétique qui ne respecte que les hommes de qualité: les historiens, les prêtres, les soldats et les révolutionnaires. Les impératifs de la géopolitique sont des constantes de l'histoire auquel l'homme de longue mémoire, seul homme valable, seul homme pourvu de qualités indépassables, se doit d'obéir. A la suite de ce Snessarev, qu'il a sans doute rencontré au temps où il servait d'officier de liaison auprès de l'Armée Rouge, Niedermayer, fort également de ses expériences d'iranologue, d'explorateur du Dacht-i-Lout et de spécialiste de l'Afghanistan, clef d'accès aux Indes depuis Alexandre le Grand, savait que le destin de l'Europe en général, de l'Allemagne, son cœur géographique, en particulier, se jouait en Inde (et, partant, en Perse et en Afghanistan). Une leçon que l'actualité a rendue plus vraie que jamais.

Exporter la révolution et absorber le "rimland"

Pour Niedermayer, officier allemand, ce rôle essentiel du territoire indien pose problème car son pays ne possède aucun point d'appui dans la région, ni dans son environnement immédiat. La Russie tsariste, oui, et, à sa suite, l'URSS, aussi. Par conséquent, les positions militaires soviétiques au Tadjikistan et le long de la frontière afghane, sont des atouts absolument nécessaires à l'Europe dans son ensemble, à toute la communauté des peuples de souche européenne. C'est la possession de cet atout stratégique en Asie centrale qui doit justifier, aux yeux de Niedermayer, l'indéfectible alliance germano-russe, seule garante de la survie de la culture européenne dans son ensemble. Pour les tenants du bolchevisme révolutionnaire autour de Trotski et Lénine, la solution, pour faire tomber le capitalisme, c'est-à-dire la puissance planétaire des thalassocraties libérales, réside dans la politique d'"exporter la révolution", d'agiter les populations colonisées et assujetties par un bon dosage de nationalisme et de révolution sociale. Ainsi, les puissances continentales de la "Terre du Milieu" pourront porter leurs énergies en direction du "rimland" indien, persan et arabe, réalisant du même coup les craintes formulées par Mackinder dans son discours de 1904 sur le "pivot" sibérien et centre-asiatique de l'histoire. Propos qu'il réitèrera dans son livre Democratic Ideals and Reality de 1919. Cependant, pour pouvoir libérer l'Inde et y exporter la révolution, il faut déjà un bloc continental bien soudé par l'alliance germano-soviétique, prélude à la libération de toute la masse continentale eurasiatique.

Pour structurer l'Europe: un chemin de fer à voies larges

Pour parfaire l'organisation de cette gigantesque masse continentale, il faut se rappeler et appliquer les recettes préconisées par le Ministre du Tsar, Sergueï Witte, père du Transsibérien. Dans le Berlin des années 20, un projet circule déjà et prendra corps pendant la seconde guerre mondiale: celui de réaliser un chemin de fer à voie large ("Breitspurbahn"), permettant de transporter un maximum de personnes et de marchandises, en un minimum de temps. Cette idée, venue de Witte, n'est pas entièrement morte, constitue toujours un impératif majeur pour qui veut véritablement travailler à la construction européenne: le Plan Delors, esquissé dans les coulisses de l'UE, préconisait naguère des grands travaux publics d'aménagement territorial, y compris un système ferroviaire rapide, désormais inspiré par le TGV français. En 1942, Hitler, en évoquant le Transsibérien de Witte, donne l'ordre à Fritz Todt d'étudier les possibilités de construire une "Breitspurbahn", avec des trains roulant entre 150 et 180 km/h pour le transport des marchandises et entre 200 et 250 km/h pour le transport des personnes. Le projet, confié à Todt, ne concerne pas seulement l'Europe, au sens restreint du terme, n'entend pas seulement relier entre elles les grandes métropoles européennes, mais aussi, via l'Ukraine et le Caucase, les villes d'Europe à celles de la Perse. Ces projets, qui apparaissaient à l'époque comme un peu fantasmagoriques, n'étaient nullement une manie du seul Hitler (et de son ingénieur Todt); en Union Soviétique aussi, via des romans populaires, comme ceux d'Ilf et de Petrov, on envisage la création de chemins de fer ultra-rapides, reliant la Russie à l'Extrême-Orient.

Le destin tragique du Professeur Otto Hoetzsch

Le volet purement scientifique de cet engouement pour le Grand Est sera incarné à Berlin, de 1913 à 1946 par un professeur génial, autant que modeste: Otto Hoetzsch. Il a connu un destin particulièrement tragique. Après avoir accumulé dans son institut personnel une masse de documents et de travaux sur la Russie, pendant des décennies, les bombardements sur Berlin en 1945, à la veille de l'entrée des troupes soviétiques dans la capitale allemande, ont réduit sa colossale bibliothèque à néant. Cette tragédie explique partiellement le sort misérable de tout le savoir sur la Russie et l'Union Soviétique à l'Ouest. La majeure partie des documents les plus intéressants avait été accumulée à Berlin. La misère de la soviétologie occidentale est partiellement le résultat navrant de la destruction de la bibliothèque du Prof. Hoetzsch. En 1945 et en 1946, celui-ci, âgé de 70 ans, erre seul dans Berlin, privé de sa documentation; cet homme, brisé, trouve néanmoins le courage ultime de rédiger une conférence, la dernière qu'il donnera, où il nous lègue un véritable testament politique (titre de cette conférence : "Die Eingliederung des osteuropäischen Geschichte in die Gesamtgeschichte"; = L'inclusion de l'histoire est-européenne dans l'histoire générale).

Le volet purement scientifique de cet engouement pour le Grand Est sera incarné à Berlin, de 1913 à 1946 par un professeur génial, autant que modeste: Otto Hoetzsch. Il a connu un destin particulièrement tragique. Après avoir accumulé dans son institut personnel une masse de documents et de travaux sur la Russie, pendant des décennies, les bombardements sur Berlin en 1945, à la veille de l'entrée des troupes soviétiques dans la capitale allemande, ont réduit sa colossale bibliothèque à néant. Cette tragédie explique partiellement le sort misérable de tout le savoir sur la Russie et l'Union Soviétique à l'Ouest. La majeure partie des documents les plus intéressants avait été accumulée à Berlin. La misère de la soviétologie occidentale est partiellement le résultat navrant de la destruction de la bibliothèque du Prof. Hoetzsch. En 1945 et en 1946, celui-ci, âgé de 70 ans, erre seul dans Berlin, privé de sa documentation; cet homme, brisé, trouve néanmoins le courage ultime de rédiger une conférence, la dernière qu'il donnera, où il nous lègue un véritable testament politique (titre de cette conférence : "Die Eingliederung des osteuropäischen Geschichte in die Gesamtgeschichte"; = L'inclusion de l'histoire est-européenne dans l'histoire générale).

Slaviste et historien de la Russie, Otto Hoetzsch s'était aperçu très tôt que les Européens de l'Ouest, les Occidentaux en général, ne comprenaient rien de la dynamique de l'histoire et de l'espace russes; ce que les Russes repèrent tout de suite, ce qui les navrent et les fâchent. Cette ignorance, assortie d'une prétention mal placée et d'une irrépressible et agaçante propension à donner des leçons, vaut également pour l'espace balkanique (sauf en Autriche où les instituts spécialisés dans le Sud-Est européen ont réalisé des travaux remarquables, dont les chancelleries occidentales ne tiennent jamais compte). Hoetzsch constate, dès le début de sa brillante carrière, que la presse ne produit que des articles lamentables, quand il s'agit de commenter ou de décrire les situations existantes en Russie ou en Sibérie. Il va vouloir remédier à cette lacune. A partir de 1913, il se met à rassembler une documentation, à étudier et à lire les grands classiques de la pensée politique russe, à lire les historiens russes, ce qui le conduira à fonder en 1925, quelques mois après la sortie du premier numéro de la ZfG de Haushofer, une revue spécialisée dans les questions russes et centre-asiatiques, Osteuropa. Captivé par la figure du Tsar Alexandre II, sur lequel il rédigera un maître-ouvrage, dont le manuscrit sera sauvé in extremis de la destruction à Berlin en 1945; Hoetzsch le transportait dans sa valise en fuyant Berlin en flammes. Pourquoi Alexandre II? Ce Tsar est un réformateur social, il lance la Russie sur la voie de l'industrialisation et de la modernisation, ce que ne peuvent tolérer les thalassocraties. Il périra d'ailleurs assassiné. En dépit du ressac de la Russie sous Nicolas II, de sa lourde défaite subie en 1905 face au Japon, armé par l'Angleterre et les Etats-Unis, en dépit du terrible ressac que constitue la prise du pouvoir par les Bolcheviques, l'œuvre d'Alexandre II doit, aux yeux de Hoetzsch, demeurer le modèle pour tout homme d'Etat russe digne de ce nom.

Ami des Russes blancs et "Républicain de Raison"

Hoetzsch est un libéral de gauche, proche de la sociale démocratie, mais il déteste les Bolcheviques, car, pour lui, ce sont des agents du capitalisme anglais, dans la mesure où ils détruisent l'œuvre des Tsars émancipateurs et modernistes; ils ont comploté contre ceux-ci et contre d'excellents hommes d'Etat comme Witte et Stolypine (qui sera également assassiné). Hoetzsch fréquente l'émigration blanche de Berlin, consolide son institut grâce aux collaborations des savants chassés par les Bolcheviques, mais reste ce que l'on appelait à l'époque, dans l'Allemagne de Weimar, un «Républicain de Raison» ("Vernunftrepublikaner"), ce qui le différencie évidemment d'un Oskar von Niedermayer. Son institut et sa revue connaissent un essor bien mérité au cours des années 20; ce sont des havres de savoir et d'intelligence, où coopèrent Russes et Allemands en toute fraternité. En 1933, avec l'avènement au pouvoir des nationaux socialistes, Hoetzsch cumule les malchances. Pour le nouveau pouvoir, les "Vernunftrepublikaner" sont des émanations du "marais centriste" ou, pire, des "traîtres de novembre" ("Novemberverräter") ou des "bolchevistes de salon" ("Salonbolschewisten"). L'institut de Hoetzsch est dissous. Hoetzsch est "invité" à prendre sa retraite anticipée. La fermeture de cet institut est une tragédie de premier ordre. Le destin de Hoetzsch est pire que celui de l'activiste politique et éditeur de revues nationales révolutionnaires, Ernst Niekisch. Car on peut évidemment, avec le recul, reprocher à Niekisch d'avoir été un passionné et un polémiste outrancier. Ce n'était évidemment pas le cas de Hoetzsch, qui est resté un scientifique sourcilleux.

Pour une approche grande-européenne de l'histoire

Dans la conférence qu'il prépare dès août 1945, et qu'il prononcera peu avant de mourir en 1946, dans sa chère ville de Berlin en ruines, Otto Hoetzsch nous a laissé un message qui reste parfaitement d'actualité. L'objectif de cette conférence-testament est de faire comprendre la nécessité impérieuse, après deux guerres mondiales désastreuses, de développer une vision de l'histoire, valable pour l'Europe entière, celle de l'Ouest, celle de l'Est et la Russie ("gesamteuropäische Geschichte"). Personnellement, nous estimons que les prémisses pratiques d'une telle vision grande européenne de l'histoire se situent déjà toutes en germe dans l'œuvre politique et militaire du Prince Eugène de Savoie, qui parvient à mobiliser et unir les puissances européennes devant le danger ottoman et à faire reculer la Sublime Porte sur tous les fronts, au point qu'elle perdra le contrôle de 400.000 km2 de terres européennes et russes. Le Prince Eugène a définitivement éloigné le danger turc de l'Europe centrale et a préparé la reconquête de la Crimée par Catherine la Grande. Plus jamais, après les coups portés par Eugène de Savoie, les Ottomans n'ont été victorieux en Europe et leurs alliés français n'ont plus été vraiment en mesure de grignoter le territoire impérial des Pays-Bas espagnols puis autrichiens; les Ottomans n'ont même plus été capables de servir de supplétifs à cette autre puissance anti-impériale et anti-européenne qu'était la France avant Louis XVI.

Le testament de Hoetzsch nous interpelle !

Mais le propos de Hoetzsch, dans sa dernière conférence, n'était pas d'évoquer la figure du Prince Eugène, mais de jeter les bases d'une méthodologie historique et sociologique pour l'avenir; elle devait reposer sur les acquis théoriques de Karl Lamprecht, de Gustav Schmoller (inspirateur du gaullisme dans les années 60 du 20ième siècle) et d'Otto Hintze. Il faut, disait Hoetzsch, développer une histoire intégrante et comparative pour les décennies à venir. En affirmant cela, il n'avait aucune chance de se voir exaucer en 1946, encore moins en 1948 quand, après le Coup de Prague, le Rideau de Fer s'abat sur l'Europe pour quatre décennies. En 1989, immédiatement après l'élimination du Mur de Berlin et l'ouverture des frontières austro-hongroises et inter-allemandes, l'Europe et la Russie auraient eu intérêt à remettre les propositions de Hoetzsch sur le tapis. Au niveau scientifique, des études remarquables ont été réalisées effectivement, mais rien ne semble transparaître dans la presse, faute de journalistes professionnels capables d'appliquer les leçons pédagogiques de Haushofer et de Radós. Les journalistes ne sont plus des hommes et des femmes en quête de sujets intéressants, innovateurs, mais bel et bien ceux que Serge Halimi nomme avec grande pertinence les "chiens de garde" du système. Les journaux et les revues constituaient la voie de pénétration vers le grand public dont disposaient jadis les instituts de sciences humaines et les universités; pour tout ce qui est véritablement innovateur, pour tout ce qui va à l'encontre des poncifs répétés ad nauseam, cette voie est désormais bien verrouillée, dans la mesure où les journalistes ne sont plus des hommes libres, animés par la volonté de consolider le Bien public, mais d'ignobles et méprisables mercenaires à la solde du système et des puissances dominantes. Toutefois, le défi que nous a lancé Brzezinski en 1996, en publiant son fameux livre, The Grand Chessboard, où sont étalées sans vergogne toutes les recettes thalassocratiques pour neutraliser l'Europe et la Russie, avec l'aide de cet instrument qu'est le complexe militaro-mafieux turc, —potentiellement étendu à toute la turcophonie d'Asie centrale— montre une nouvelle fois qu'une riposte européenne et russe doit nécessairement passer par une vision claire de l'histoire, vulgarisable pour les masses. Le destin tragique de Hoetzsch, son courage opiniâtre qui force l'admiration, sa modestie de grand savant, nous interpellent directement: notre amicale paneuropéenne a pour devoir de travailler, modestement, dans son créneau, à l'avènement de cette historiographie grande européenne que Hoetzsch a voulu. Au travail!

Robert STEUCKERS.

(Forest-Flotzenberg, Vlotho im Weserbergland, août 2002).

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Outre Haushofer, une approche du savoir géopolitique, tel qu'il sera déployé à Berlin dans les années 20, 30 et 40, ne peut omettre d'étudier la figure du Chevalier Oskar von Niedermayer, celui que l'on avait surnommé, le "Lawrence d'Arabie" allemand. Né en 1885, Oskar von Niedermayer embrasse la carrière d'officier, mais ne se contente pas des simples servitudes militaires. Il étudie à l'université les sciences naturelles physiques, la géographie et les langues iraniennes (ce qui lui permettra d'avoir des contacts suivis avec la Communauté religieuse Ba'hai, qui, à l'époque, était quasiment la seule porte ouverte de l'Iran sur l'Occident). De 1912 à 1914, il effectue un long voyage en Perse et en Inde. Il sera ainsi le premier Européen à traverser de part en part le désert de sable du Lout (Dacht-i-Lout). En 1914, quand éclate la première guerre mondiale, Oskar von Niedermayer, accompagné par Werner Otto von Henting, sillonne les montagnes d'Afghanistan pour inciter les tribus afghanes à se soulever contre les Anglais et les Russes, afin de créer un "abcès de fixation", obligeant les deux puissances ennemies de l'Allemagne à dégarnir partiellement

Outre Haushofer, une approche du savoir géopolitique, tel qu'il sera déployé à Berlin dans les années 20, 30 et 40, ne peut omettre d'étudier la figure du Chevalier Oskar von Niedermayer, celui que l'on avait surnommé, le "Lawrence d'Arabie" allemand. Né en 1885, Oskar von Niedermayer embrasse la carrière d'officier, mais ne se contente pas des simples servitudes militaires. Il étudie à l'université les sciences naturelles physiques, la géographie et les langues iraniennes (ce qui lui permettra d'avoir des contacts suivis avec la Communauté religieuse Ba'hai, qui, à l'époque, était quasiment la seule porte ouverte de l'Iran sur l'Occident). De 1912 à 1914, il effectue un long voyage en Perse et en Inde. Il sera ainsi le premier Européen à traverser de part en part le désert de sable du Lout (Dacht-i-Lout). En 1914, quand éclate la première guerre mondiale, Oskar von Niedermayer, accompagné par Werner Otto von Henting, sillonne les montagnes d'Afghanistan pour inciter les tribus afghanes à se soulever contre les Anglais et les Russes, afin de créer un "abcès de fixation", obligeant les deux puissances ennemies de l'Allemagne à dégarnir partiellement Le volet purement scientifique de cet engouement pour le Grand Est sera incarné à Berlin, de 1913 à 1946 par un professeur génial, autant que modeste: Otto Hoetzsch. Il a connu un destin particulièrement tragique. Après avoir accumulé dans son institut personnel une masse de documents et de travaux sur la Russie, pendant des décennies, les bombardements sur Berlin en 1945, à la veille de l'entrée des troupes soviétiques dans la capitale allemande, ont réduit sa colossale bibliothèque à néant. Cette tragédie explique partiellement le sort misérable de tout le savoir sur la Russie et l'Union Soviétique à l'Ouest. La majeure partie des documents les plus intéressants avait été accumulée à Berlin. La misère de la soviétologie occidentale est partiellement

Le volet purement scientifique de cet engouement pour le Grand Est sera incarné à Berlin, de 1913 à 1946 par un professeur génial, autant que modeste: Otto Hoetzsch. Il a connu un destin particulièrement tragique. Après avoir accumulé dans son institut personnel une masse de documents et de travaux sur la Russie, pendant des décennies, les bombardements sur Berlin en 1945, à la veille de l'entrée des troupes soviétiques dans la capitale allemande, ont réduit sa colossale bibliothèque à néant. Cette tragédie explique partiellement le sort misérable de tout le savoir sur la Russie et l'Union Soviétique à l'Ouest. La majeure partie des documents les plus intéressants avait été accumulée à Berlin. La misère de la soviétologie occidentale est partiellement

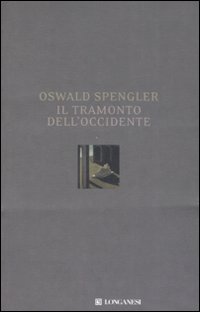

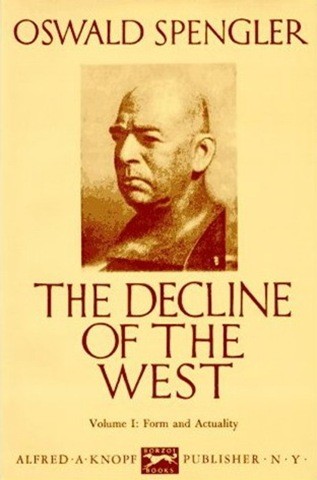

The pages devoted to Spengler in The Path of Cinnabar are thus quite critical; Evola even concludes that the influence of Spengler on his thought was null. Such is not the opinion of an analyst of Spengler and Evola, Attilio Cucchi (in “Evola, Tradizione e Spengler,” Orion no. 89, 1992). For Cucchi, Spengler influenced Evola, particularly in his criticism of the concept of the “West”: by affirming that Western civilization is not the civilization, the only civilization there is, Spengler relativizes it, as Guénon charges. Evola, an attentive reader of Spengler and Guénon, would combine elements of the the Spenglerian and Guénonian critiques. Spengler affirms that Faustian Western culture, which began in the tenth century, has declined and fallen into Zivilisation, which has frozen, drained, and killed its inner energy. America is already at this final stage of de-ruralized and technological Zivilisation.

The pages devoted to Spengler in The Path of Cinnabar are thus quite critical; Evola even concludes that the influence of Spengler on his thought was null. Such is not the opinion of an analyst of Spengler and Evola, Attilio Cucchi (in “Evola, Tradizione e Spengler,” Orion no. 89, 1992). For Cucchi, Spengler influenced Evola, particularly in his criticism of the concept of the “West”: by affirming that Western civilization is not the civilization, the only civilization there is, Spengler relativizes it, as Guénon charges. Evola, an attentive reader of Spengler and Guénon, would combine elements of the the Spenglerian and Guénonian critiques. Spengler affirms that Faustian Western culture, which began in the tenth century, has declined and fallen into Zivilisation, which has frozen, drained, and killed its inner energy. America is already at this final stage of de-ruralized and technological Zivilisation.

Conceived before the First World War is Oswald Spengler’s magisterial work, Der Untergang des Abendlandes (Munich, 1918). Read in this country chiefly in the brilliantly faithful translation by Charles Francis Atkinson, The Decline of the West (New York, two volumes, 1926-28), Spengler’s morphology of history was the great intellectual achievement of our century. Whatever our opinion of his methods or conclusions, we cannot deny that he was the Copernicus of historionomy. All subsequent writings on the philosophy of history may fairly be described as criticism of the Decline of the West.

Conceived before the First World War is Oswald Spengler’s magisterial work, Der Untergang des Abendlandes (Munich, 1918). Read in this country chiefly in the brilliantly faithful translation by Charles Francis Atkinson, The Decline of the West (New York, two volumes, 1926-28), Spengler’s morphology of history was the great intellectual achievement of our century. Whatever our opinion of his methods or conclusions, we cannot deny that he was the Copernicus of historionomy. All subsequent writings on the philosophy of history may fairly be described as criticism of the Decline of the West. The exception becomes even more remarkable if we, unlike Spengler, regard as fundamentally important the concept of self-government, which may have been present even in Mycenaean times (see L. R. Palmer, Mycenaeans and Minoans, cited above, p. 97). Democracies and constitutional republics are found only in the Graeco-Roman world and our own; such institutions seem to have been incomprehensible to other cultures.

The exception becomes even more remarkable if we, unlike Spengler, regard as fundamentally important the concept of self-government, which may have been present even in Mycenaean times (see L. R. Palmer, Mycenaeans and Minoans, cited above, p. 97). Democracies and constitutional republics are found only in the Graeco-Roman world and our own; such institutions seem to have been incomprehensible to other cultures.

Ernst Jünger (1895-1998), autor de diarios claves sobre lo que se llamó la estética del horror, así como de un importante ensayo -El Trabajador- acerca de la cultura de la técnica moderna y sus repercusiones, está considerado, incluso por sus críticos más acerbos, como un gran estilista del idioma alemán, al que algunos incluso ponen a la altura de los grandes clásicos de la literatura germánica. Fue el último sobreviviente de una generación de intelectuales heredada de la obra de Oswald Spengler, Martin Heidegger, Carl Schmitt y Gottfried Benn. Apasionado polemista, nunca estuvo ajeno de la controversia política e ideológica de su patria; iconoclasta paradójico, enemigo del eufemismo, "anarquista reaccionario" en sus propias palabras, abominador de las dictaduras (fue expulsado del ejército alemán en 1944 después del fracaso del movimiento antihitlerista) y las democracias (dictaduras de la mayoría, como las llamó Karl Kraus, líder espiritual del círculo de Viena). En 1981, Jünger recibió el premio Goethe en Frankfurt, máximo galardón literario de la lengua germana. Sus obras, varias de ellas de carácter biográfico, giran sobre el eje de protagonistas en cuyas almas el autor intenta plasmar una cierta soledad y desencantamiento frente al mundo contemporáneo; al tema central, intercala disquisiciones acerca del origen y destino del hombre, filosofía de la historia, naturaleza del Estado y la sociedad. Por sobre esto, sus obras constituyen un llamado de denuncia y advertencia ante el avance incontenible y abrasador del nihilismo como movimiento mundial, a la vez que se convierten en guías para las almas rebeldes ante este proceso avasallador.

Ernst Jünger (1895-1998), autor de diarios claves sobre lo que se llamó la estética del horror, así como de un importante ensayo -El Trabajador- acerca de la cultura de la técnica moderna y sus repercusiones, está considerado, incluso por sus críticos más acerbos, como un gran estilista del idioma alemán, al que algunos incluso ponen a la altura de los grandes clásicos de la literatura germánica. Fue el último sobreviviente de una generación de intelectuales heredada de la obra de Oswald Spengler, Martin Heidegger, Carl Schmitt y Gottfried Benn. Apasionado polemista, nunca estuvo ajeno de la controversia política e ideológica de su patria; iconoclasta paradójico, enemigo del eufemismo, "anarquista reaccionario" en sus propias palabras, abominador de las dictaduras (fue expulsado del ejército alemán en 1944 después del fracaso del movimiento antihitlerista) y las democracias (dictaduras de la mayoría, como las llamó Karl Kraus, líder espiritual del círculo de Viena). En 1981, Jünger recibió el premio Goethe en Frankfurt, máximo galardón literario de la lengua germana. Sus obras, varias de ellas de carácter biográfico, giran sobre el eje de protagonistas en cuyas almas el autor intenta plasmar una cierta soledad y desencantamiento frente al mundo contemporáneo; al tema central, intercala disquisiciones acerca del origen y destino del hombre, filosofía de la historia, naturaleza del Estado y la sociedad. Por sobre esto, sus obras constituyen un llamado de denuncia y advertencia ante el avance incontenible y abrasador del nihilismo como movimiento mundial, a la vez que se convierten en guías para las almas rebeldes ante este proceso avasallador.

Gabriele d'Annunzio (1863-1938), au temps de la “Belle époque”, était le seul poète italien connu dans le monde entier. Après la première guerre mondiale, sa gloire est devenue plutôt “muséale”, sans doute parce qu'il l'a lui-même voulu. Il devint ainsi “Prince de Montenevoso”. Un institut d'Etat édita ses œuvres complètes en 49 volumes. Surtout, il tranforma la Villa Cargnacco, sur les rives du Lac de Garde, en un mausolée tout à fait particulier (“Il Vittoriale degli Italiani”) qui, après la seconde guerre mondiale, a attiré plus de touristes que ses livres de lecteurs. En Allemagne, d'Annunzio a dû être tiré de l'oubli en 1988 par l'éditeur non-conformiste de Munich, Matthes & Seitz, et par un volume de la célèbre collection de monographies “rororo”. Aujourd'hui, coup de théâtre, un volume collectif rédigé par des philosophes et des philologues nous confirme que la grand “décadant” a sans doute été le “dernier poète-souverain de l'histoire” (références infra). A quel autre écrivain pourrait-on donner ce titre?

Gabriele d'Annunzio (1863-1938), au temps de la “Belle époque”, était le seul poète italien connu dans le monde entier. Après la première guerre mondiale, sa gloire est devenue plutôt “muséale”, sans doute parce qu'il l'a lui-même voulu. Il devint ainsi “Prince de Montenevoso”. Un institut d'Etat édita ses œuvres complètes en 49 volumes. Surtout, il tranforma la Villa Cargnacco, sur les rives du Lac de Garde, en un mausolée tout à fait particulier (“Il Vittoriale degli Italiani”) qui, après la seconde guerre mondiale, a attiré plus de touristes que ses livres de lecteurs. En Allemagne, d'Annunzio a dû être tiré de l'oubli en 1988 par l'éditeur non-conformiste de Munich, Matthes & Seitz, et par un volume de la célèbre collection de monographies “rororo”. Aujourd'hui, coup de théâtre, un volume collectif rédigé par des philosophes et des philologues nous confirme que la grand “décadant” a sans doute été le “dernier poète-souverain de l'histoire” (références infra). A quel autre écrivain pourrait-on donner ce titre?

Ernst Niekisch è la figura più rappresentativa del complesso e multiforme panorama che offre il movimento nazional-bolscevico tedesco degli anni 1918-1933. In lui si incarnano con chiarezza le caratteristiche - e le contraddizioni - evocate dal termine nazional-bolscevico e che rispondono molto più ad uno stato d'animo, ad una disposizione attivista, che ad una ideologia dai contorni precisi o ad una unità organizzativa, poiché questo movimento era composto da una infinità di piccoli circoli, gruppi, riviste ecc. senza che ci fosse mai stato un partito che si fosse qualificato nazional-bolscevico. E’ curioso constatare come nessuno di questi gruppi o persone usò questo appellativo (se escludiamo la rivista di Karl Otto Paetel, "Die Sozialistische Nation") bensì che l’aggettivo fu impiegato in modo dispregiativo, non scevro di sensazionalismo, dalla stampa e dai partiti sostenitori della Repubblica di Weimar, dei quali tutti i nazional-bolscevichi furono feroci nemici non essendoci sotto questo punto di vista differenze fra gruppi d’origine comunista che assimilarono l’idea nazionale ed i gruppi nazionalisti disposti a perseguire scambi economici radicali e l’alleanza con l'URSS per distruggere l'odiato sistema nato dal Diktat di Versailles. Ernst Niekisch nacque il 23 maggio 1889 a Trebnitz (Slesia). Era figlio di un limatore che si trasferì a Nordlingen im Reis (Baviera-Svevia) nel 1891. Niekisch frequenta gli studi di magistero, che termina nel 1907, esercitando poi a Ries e Augsburg. Non era frequente nella Germania guglielmina - quello Stato in cui si era realizzata la vittoria del borghese sul soldato secondo Carl Schmitt - che il figlio di un operaio studiasse, per cui Niekisch dovette soffrire le burle e l’ostilità dei suoi compagni di scuola. Già in quel periodo era avido di sapere ("Una vita da nullità è insopportabile", dirà) e divorato da un interiore fuoco rivoluzionario; legge Hauptmann, Ibsen, Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, Kant, Hegel e Macchiavelli, alla cui influenza si aggiungerà quella di Marx, a partire dal 1915. Arruolato nell’esercito nel 1914, seri problemi alla vista gli impediscono di giungere al fronte, per cui eserciterà, sino al febbraio del 1917, funzioni di istruttore di reclute ad Augsburg. Nell’ottobre del 1917 entra nel Partito Socialdemocratico (SPD) e si sente fortemente attratto dalla rivoluzione bolscevica. E' di quell’epoca il suo primo scritto politico, oggi perso, intitolato significativamente Licht aus dem osten (Luce dall’Est), nel quale già formulava ciò che sarà una costante della sua azione politica: l’idea della "Ostorientierung". La diffusione di questo foglio sarà sabotata dallo stesso SPD al cui periodico di Augsburg "Schwabischen Volkszeitung" collaborava Niekisch. Il 7 novembre 1918 Eisner, a Monaco, proclama la Repubblica. Niekisch fonda il Consiglio degli Operai e Soldati di Augsburg e ne diviene il presidente, dopo esserlo già stato del Consiglio Centrale degli Operai, Contadini e Soldati di Monaco nel febbraio e nel marzo del 1919. Egli è l’unico membro del Comitato Centrale che vota contro la proclamazione della prima Repubblica sovietica in Baviera, poiché considera che questa, in ragione del suo carattere agrario, sia la provincia tedesca meno idonea a realizzare l’esperimento. Malgrado ciò, con l’entrata dei Freikorps a Monaco, Niekisch viene arrestato il 5 maggio - giorno in cui passa dal SPD al Partito Socialdemocratico Indipendente (USPD). lI 22 giugno viene condannato a due anni di fortezza per la sua attività nel Consiglio degli Operai e Soldati, per quanto non abbia avuto nulla a che vedere con i crimini della Repubblica sovietica bavarese. Niekisch sconta integralmente la sua pena, e nonostante l’elezione al parlamento bavarese nelle liste della USPD non sarà liberato fino all’agosto del 1921. Frattanto, si ritrova nel SPD per effetto della riunificazione dello stesso con la USPD (la scissione si era determinata durante la guerra mondiale). Niekisch non è assolutamente d’accordo con la politica condiscendente dell’SPD - per temperamento era incapace di sopportare le mezze tinte o i compromessi - ed a questa situazione di sdegno si aggiungevano le minacce contro di lui e la sua famiglia (si era sposato nel 1915 ed aveva un figlio); così rinuncia al suo mandato parlamentare e si trasferisce a Berlino, dove entra nella direzione della segreteria giovanile del grande sindacato dei tessili, un lavoro burocratico che non troverà di suo gradimento. I suoi rapporti con L'SPD si deteriorano progressivamente, per il fatto che Niekisch si oppone al pagamento dei danni di guerra alla Francia e al Belgio e appoggia la resistenza nazionale quando la Francia occupa il bacino della Ruhr, nel gennaio del 1923. Dal 1924 si oppone anche al Piano Dawes, che regola il pagamento dei danni di guerra imposto alla Germania a Versailles. Niekisch attaccò frontalmente la posizione dell’SPD di accettazione del Piano Dawes in una conferenza di sindacalisti e socialdemocratici scontrandosi con Franz Hilferding, principale rappresentante della linea ufficiale.

Ernst Niekisch è la figura più rappresentativa del complesso e multiforme panorama che offre il movimento nazional-bolscevico tedesco degli anni 1918-1933. In lui si incarnano con chiarezza le caratteristiche - e le contraddizioni - evocate dal termine nazional-bolscevico e che rispondono molto più ad uno stato d'animo, ad una disposizione attivista, che ad una ideologia dai contorni precisi o ad una unità organizzativa, poiché questo movimento era composto da una infinità di piccoli circoli, gruppi, riviste ecc. senza che ci fosse mai stato un partito che si fosse qualificato nazional-bolscevico. E’ curioso constatare come nessuno di questi gruppi o persone usò questo appellativo (se escludiamo la rivista di Karl Otto Paetel, "Die Sozialistische Nation") bensì che l’aggettivo fu impiegato in modo dispregiativo, non scevro di sensazionalismo, dalla stampa e dai partiti sostenitori della Repubblica di Weimar, dei quali tutti i nazional-bolscevichi furono feroci nemici non essendoci sotto questo punto di vista differenze fra gruppi d’origine comunista che assimilarono l’idea nazionale ed i gruppi nazionalisti disposti a perseguire scambi economici radicali e l’alleanza con l'URSS per distruggere l'odiato sistema nato dal Diktat di Versailles. Ernst Niekisch nacque il 23 maggio 1889 a Trebnitz (Slesia). Era figlio di un limatore che si trasferì a Nordlingen im Reis (Baviera-Svevia) nel 1891. Niekisch frequenta gli studi di magistero, che termina nel 1907, esercitando poi a Ries e Augsburg. Non era frequente nella Germania guglielmina - quello Stato in cui si era realizzata la vittoria del borghese sul soldato secondo Carl Schmitt - che il figlio di un operaio studiasse, per cui Niekisch dovette soffrire le burle e l’ostilità dei suoi compagni di scuola. Già in quel periodo era avido di sapere ("Una vita da nullità è insopportabile", dirà) e divorato da un interiore fuoco rivoluzionario; legge Hauptmann, Ibsen, Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, Kant, Hegel e Macchiavelli, alla cui influenza si aggiungerà quella di Marx, a partire dal 1915. Arruolato nell’esercito nel 1914, seri problemi alla vista gli impediscono di giungere al fronte, per cui eserciterà, sino al febbraio del 1917, funzioni di istruttore di reclute ad Augsburg. Nell’ottobre del 1917 entra nel Partito Socialdemocratico (SPD) e si sente fortemente attratto dalla rivoluzione bolscevica. E' di quell’epoca il suo primo scritto politico, oggi perso, intitolato significativamente Licht aus dem osten (Luce dall’Est), nel quale già formulava ciò che sarà una costante della sua azione politica: l’idea della "Ostorientierung". La diffusione di questo foglio sarà sabotata dallo stesso SPD al cui periodico di Augsburg "Schwabischen Volkszeitung" collaborava Niekisch. Il 7 novembre 1918 Eisner, a Monaco, proclama la Repubblica. Niekisch fonda il Consiglio degli Operai e Soldati di Augsburg e ne diviene il presidente, dopo esserlo già stato del Consiglio Centrale degli Operai, Contadini e Soldati di Monaco nel febbraio e nel marzo del 1919. Egli è l’unico membro del Comitato Centrale che vota contro la proclamazione della prima Repubblica sovietica in Baviera, poiché considera che questa, in ragione del suo carattere agrario, sia la provincia tedesca meno idonea a realizzare l’esperimento. Malgrado ciò, con l’entrata dei Freikorps a Monaco, Niekisch viene arrestato il 5 maggio - giorno in cui passa dal SPD al Partito Socialdemocratico Indipendente (USPD). lI 22 giugno viene condannato a due anni di fortezza per la sua attività nel Consiglio degli Operai e Soldati, per quanto non abbia avuto nulla a che vedere con i crimini della Repubblica sovietica bavarese. Niekisch sconta integralmente la sua pena, e nonostante l’elezione al parlamento bavarese nelle liste della USPD non sarà liberato fino all’agosto del 1921. Frattanto, si ritrova nel SPD per effetto della riunificazione dello stesso con la USPD (la scissione si era determinata durante la guerra mondiale). Niekisch non è assolutamente d’accordo con la politica condiscendente dell’SPD - per temperamento era incapace di sopportare le mezze tinte o i compromessi - ed a questa situazione di sdegno si aggiungevano le minacce contro di lui e la sua famiglia (si era sposato nel 1915 ed aveva un figlio); così rinuncia al suo mandato parlamentare e si trasferisce a Berlino, dove entra nella direzione della segreteria giovanile del grande sindacato dei tessili, un lavoro burocratico che non troverà di suo gradimento. I suoi rapporti con L'SPD si deteriorano progressivamente, per il fatto che Niekisch si oppone al pagamento dei danni di guerra alla Francia e al Belgio e appoggia la resistenza nazionale quando la Francia occupa il bacino della Ruhr, nel gennaio del 1923. Dal 1924 si oppone anche al Piano Dawes, che regola il pagamento dei danni di guerra imposto alla Germania a Versailles. Niekisch attaccò frontalmente la posizione dell’SPD di accettazione del Piano Dawes in una conferenza di sindacalisti e socialdemocratici scontrandosi con Franz Hilferding, principale rappresentante della linea ufficiale. Fortemente influenzato da Carl Schmitt, e partendo da questa base, Niekisch doveva vedere come nemico irriducibile il liberalismo borghese, che valorizza soprattutto i principi economici e considera l'uomo soltanto isolatamente, come unità alla ricerca del suo esclusivo profitto. l'individualismo borghese (con i conseguenti Stato liberale di diritto, libertà individuali, considerazioni dello Stato come un male) e materialismo nel pensiero di Niekisch appaiono come caratteristiche essenziali della democrazia borghese. Nello stesso tempo, Niekisch sviluppa una critica non originale, ma efficace e sincera, del sistema capitalista come sistema il cui motore è l’utile privato e non il soddisfacimento delle necessità individuali e collettive; e che, per di più, genera continuamente disoccupazione. In questo modo la borghesia viene qualificata come nemico interno che collabora con gli Stati occidentali borghesi all’oppressione della Germania. Il sistema di Weimar (incarnato da democratici, socialisti e clericali) rappresentava l’opposto dello spirito e della volontà statale dei tedeschi, ed era il nemico contro il quale si doveva organizzare la “Resistenza". Quello di "Resistenza" è un'altro concetto fondamentale dell'opera di Niekisch. La rivista dallo stesso nome recava, oltre al sottotitolo (prima "Blätter für sozialistische und nationalrevolutionäre Politik", quindi "Zeitschrift für nationalrevolutionäre Politik") una significativa frase di Clausewitz: "La resistenza è un'attività mediante la quale devono essere distrutte tante forze del nemico da indurlo a rinunciare ai suoi propositi". Se Niekisch considerava possibile questa attitudine di resistenza è perché credeva che la situazione di decadenza della Germania fosse passeggera, non irreversibile; e per quanto a volte sottolineasse che il suo pessimismo era “illimitato", si devono considerare le sue dichiarazioni in questo senso come semplici espedienti retorici, poiché la sua continua attività rivoluzionaria è la prova migliore che in nessun momento cedette al pessimismo ed allo sconforto. Abbiamo visto qual era il nemico contro cui dover organizzare la resistenza: “La democrazia parlamentare ed il liberalismo, il modo di vivere francese e l’americanismo". Con la stessa esattezza Niekisch definisce gli obiettivi della resistenza: l’indipendenza e la libertà della Germania, la più alta valorizzazione dello Stato, il recupero di tutti i tedeschi che si trovavano sorto il dominio straniero. Coerente col suo rifiuto dei valori economici, Niekisch non contrappone a questo nemico una forma migliore di distribuzione dei beni materiali, né il conseguimento di una società del benessere: ciò che Niekisch cercava era il superamento del mondo borghese, i cui beni si devono “detestare asceticamente". Il programma di "Resistenza" dell’aprile del 1930 non lascia dubbi da questo punto di vista: nello stesso si chiede il rifiuto deciso di tutti i beni che l’Europa vagheggia (punto 7a), il ritiro dall'economia internazionale (punto 7b), la riduzione della popolazione urbana e la ricostituzione delle possibilità di vita contadina (7c-d), la volontà di povertà ed un modo di vita semplice che deve opporsi orgogliosamente alla vita raffinata delle potenze imperialiste occidentali (7f) e, finalmente, la rinuncia al principio della proprietà privata nel senso del diritto romano, poiché “agli occhi dell’opposizione nazionale, la proprietà non ha senso né diritto al di fuori del servizio al popolo ed allo Stato”. Per realizzare i suoi obiettivi, che Uwe Sauermann definisce con precisione identici a quelli dei nazionalisti, anche se le strade e gli strumenti per conseguirli sono nuovi, Niekisch cerca le forze rivoluzionarie adeguate. Non può sorprendere che un uomo proveniente dalla sinistra come lui si diriga in primo luogo al movimento operaio.

Fortemente influenzato da Carl Schmitt, e partendo da questa base, Niekisch doveva vedere come nemico irriducibile il liberalismo borghese, che valorizza soprattutto i principi economici e considera l'uomo soltanto isolatamente, come unità alla ricerca del suo esclusivo profitto. l'individualismo borghese (con i conseguenti Stato liberale di diritto, libertà individuali, considerazioni dello Stato come un male) e materialismo nel pensiero di Niekisch appaiono come caratteristiche essenziali della democrazia borghese. Nello stesso tempo, Niekisch sviluppa una critica non originale, ma efficace e sincera, del sistema capitalista come sistema il cui motore è l’utile privato e non il soddisfacimento delle necessità individuali e collettive; e che, per di più, genera continuamente disoccupazione. In questo modo la borghesia viene qualificata come nemico interno che collabora con gli Stati occidentali borghesi all’oppressione della Germania. Il sistema di Weimar (incarnato da democratici, socialisti e clericali) rappresentava l’opposto dello spirito e della volontà statale dei tedeschi, ed era il nemico contro il quale si doveva organizzare la “Resistenza". Quello di "Resistenza" è un'altro concetto fondamentale dell'opera di Niekisch. La rivista dallo stesso nome recava, oltre al sottotitolo (prima "Blätter für sozialistische und nationalrevolutionäre Politik", quindi "Zeitschrift für nationalrevolutionäre Politik") una significativa frase di Clausewitz: "La resistenza è un'attività mediante la quale devono essere distrutte tante forze del nemico da indurlo a rinunciare ai suoi propositi". Se Niekisch considerava possibile questa attitudine di resistenza è perché credeva che la situazione di decadenza della Germania fosse passeggera, non irreversibile; e per quanto a volte sottolineasse che il suo pessimismo era “illimitato", si devono considerare le sue dichiarazioni in questo senso come semplici espedienti retorici, poiché la sua continua attività rivoluzionaria è la prova migliore che in nessun momento cedette al pessimismo ed allo sconforto. Abbiamo visto qual era il nemico contro cui dover organizzare la resistenza: “La democrazia parlamentare ed il liberalismo, il modo di vivere francese e l’americanismo". Con la stessa esattezza Niekisch definisce gli obiettivi della resistenza: l’indipendenza e la libertà della Germania, la più alta valorizzazione dello Stato, il recupero di tutti i tedeschi che si trovavano sorto il dominio straniero. Coerente col suo rifiuto dei valori economici, Niekisch non contrappone a questo nemico una forma migliore di distribuzione dei beni materiali, né il conseguimento di una società del benessere: ciò che Niekisch cercava era il superamento del mondo borghese, i cui beni si devono “detestare asceticamente". Il programma di "Resistenza" dell’aprile del 1930 non lascia dubbi da questo punto di vista: nello stesso si chiede il rifiuto deciso di tutti i beni che l’Europa vagheggia (punto 7a), il ritiro dall'economia internazionale (punto 7b), la riduzione della popolazione urbana e la ricostituzione delle possibilità di vita contadina (7c-d), la volontà di povertà ed un modo di vita semplice che deve opporsi orgogliosamente alla vita raffinata delle potenze imperialiste occidentali (7f) e, finalmente, la rinuncia al principio della proprietà privata nel senso del diritto romano, poiché “agli occhi dell’opposizione nazionale, la proprietà non ha senso né diritto al di fuori del servizio al popolo ed allo Stato”. Per realizzare i suoi obiettivi, che Uwe Sauermann definisce con precisione identici a quelli dei nazionalisti, anche se le strade e gli strumenti per conseguirli sono nuovi, Niekisch cerca le forze rivoluzionarie adeguate. Non può sorprendere che un uomo proveniente dalla sinistra come lui si diriga in primo luogo al movimento operaio.

Indeed, as Griffin makes clear, fascists and para-fascists are usually, by their very nature, bitter enemies. While para-fascists may co-opt some superficial characteristics of their fascist opponents, in power they tend to ruthlessly suppress the expression of revolutionary fascism. When para-fascism attempts to co-opt fascism by sharing power – as Antonescu attempted in Romania with the Legionaries — conflict is inevitable, since the objectives of the two parties are completely different: para-fascist ossification vs. fascist palingenetic regeneration. Thus, in Romania, civil war between para-fascists and fascists led to the victory of the para-fascists, and the exile of the fascist forces. The idea that Antonescu was “fascist” is a byproduct of either ideological ignorance or ideological mendacity, a Marxist desire to strip their fascist competitors of revolutionary dynamism and reduce them to mere “bourgeois hooligans.”

Indeed, as Griffin makes clear, fascists and para-fascists are usually, by their very nature, bitter enemies. While para-fascists may co-opt some superficial characteristics of their fascist opponents, in power they tend to ruthlessly suppress the expression of revolutionary fascism. When para-fascism attempts to co-opt fascism by sharing power – as Antonescu attempted in Romania with the Legionaries — conflict is inevitable, since the objectives of the two parties are completely different: para-fascist ossification vs. fascist palingenetic regeneration. Thus, in Romania, civil war between para-fascists and fascists led to the victory of the para-fascists, and the exile of the fascist forces. The idea that Antonescu was “fascist” is a byproduct of either ideological ignorance or ideological mendacity, a Marxist desire to strip their fascist competitors of revolutionary dynamism and reduce them to mere “bourgeois hooligans.” In some sense, perhaps the “purest” brand of fascism was that of

In some sense, perhaps the “purest” brand of fascism was that of With respect to Antliff’s book itself, chapter topics include